Agora Notebooks

Overview

The Agora Notebooks are the primary records of the Athenian Agora Excavations of the American School of Classical Studies in Greece (http://agathe.gr).

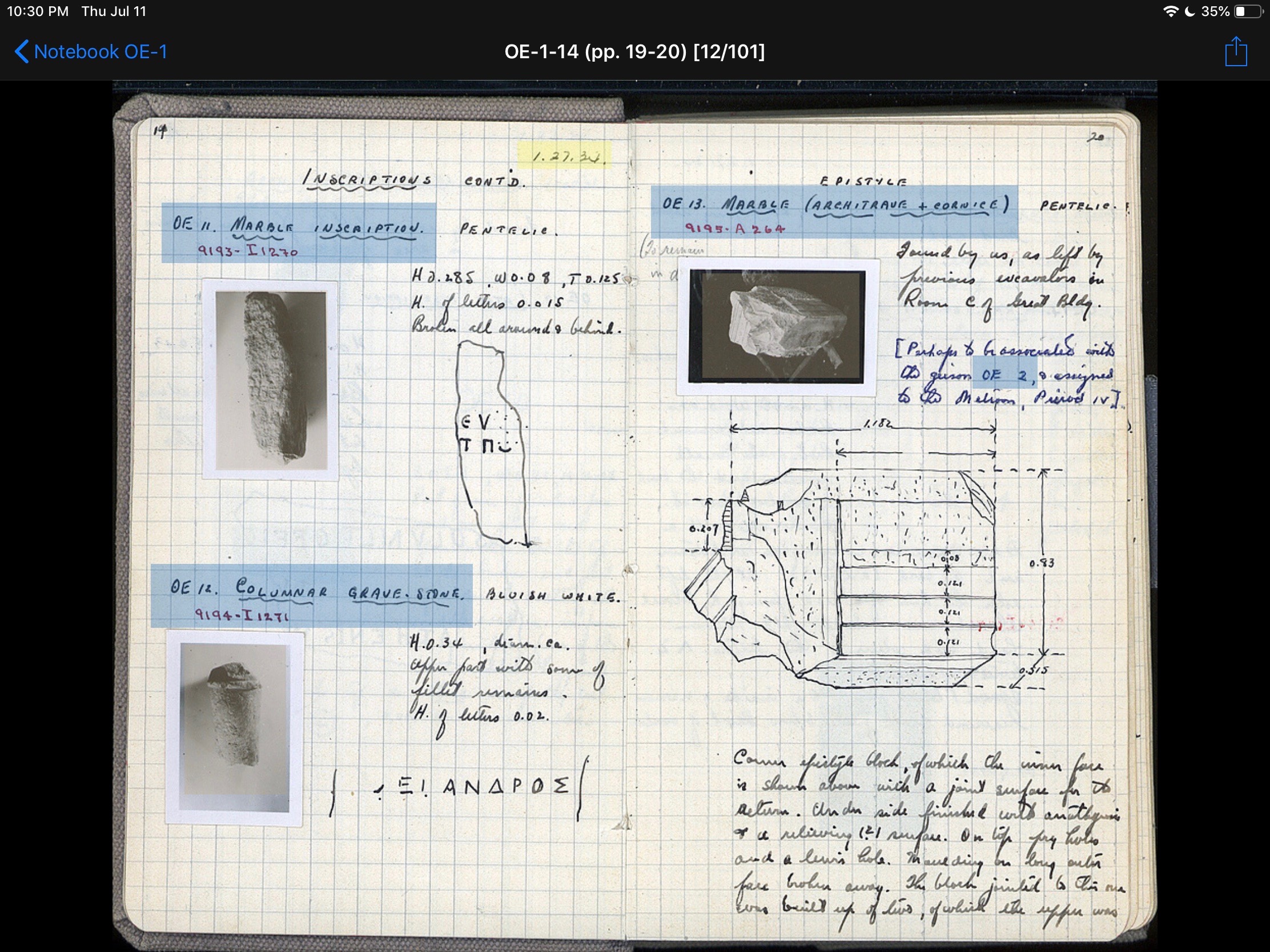

The notebooks contain photographs, drawings, and original field notes, making it possible to recover the archaeological context of every object found.

The version of the Agora Notebooks released here contains 319 publicly available notebooks. You can browse the notebooks, use the annotations for navigation, and download the notebooks for offline reading.

Some of the areas at the Agora are still under study and are being prepared for publication. For the time being, those scholars with a confirmed active publication assignment may contact the Agora offices for a username and password to access all 937 notebooks. There are limitations as to the use of such access.

This app was created by Bruce Hartzler and made possible with the collaboration of The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) and with a grant from the European Economic Area (EEA).

The Archives of Athens

By John McK Camp IIDirector of the Athenian Agora Excavations

In antiquity, the Athenian Agora was a center of record-keeping and publication of documents for centuries. The ready availability of public records is a mark of a highly democratic society, especially in the case of Athens, where almost the entire government changed every year. Corinth has produced relatively few inscriptions compared to more than 7,500 from the Agora. The discrepancy is presumably reflective of the differing needs of an oligarchic political system as opposed to a democracy.

A major event in this history of democracy occurred when the axones and kurbeis, the old written laws of Solon, were transferred by Ephialtes from the acropolis to the bouleuterion in the Agora in the lower city in the years around 461 BC. Henceforth, the record of the laws of Athens was to be available to any citizen, not just aristocratic magistrates.

This use of the bouleuterion as the repository of Athenian laws dates to the middle years of the 5th century. When a new bouleuterion was built at the end of the 5th century, the old one continued as an archive, now under the protection of the Mother of the Gods, and the building became known as the Metroon. Not only laws, but decrees, records of lawsuits, records of expenditures, and wills were deposited there. The old Metroon was rebuilt in the years around 150 BC, and it continued in use as the archives of the city into the 1st century AD. Indeed, the name still survives in modern Greek for some forms of lists and other archival material. The same deity was responsible for the public archives of the city of Kolophon, in Asia Minor.

Public display of documents, rather than just access or archiving, was also a concern by the late 5th century BC. At the end of the century, a complete copy of the Athenian law code or constitution was created by an appointed nomothetes, Nikomachos. The laws were then inscribed on numerous marble stelai, and set up on public display at the Royal Stoa, headquarters of the Archon Basileios, chief legal magistrate of the city. Numerous fragments of this law code have been recovered and studied.

A third instance of the dissemination of public information in ancient Athens was to be found just across from the Metroon, the official archive building. This was the Monument of the Eponymous Heroes, where notices concerning Athenian citizens would be posted beneath the statue of the appropriate tribal hero. Military conscription, upcoming legal events, public honors, and proposed legislation were all put on display for anyone and everyone to read. In the days before radio and television, telephones and newspapers, the monument was essential for keeping the Athenians informed about their rights and duties as citizens.

The Athenians kept their records on a wide variety of materials, and many have been recovered in the excavations: on stone, on clay, on bronze, and on lead. Attested, but not easily recovered, are documents written on papyrus, and others written in charcoal on boards painted white. For this last, charcoal on whitened boards, we even have an account of an early attempt at hacking the records, in an anecdote mentioned by Athenaios about Alkibiades:

Alkibiades bade them have confidence, and telling them all to follow him, he went into the Metroon, where were the records of the lawsuits; and wetting his finger in his mouth, he erased the lawsuit of Hegemon. The clerk and the archon were very annoyed, but held their peace since it was Alkibiades; the prosecutor took the precaution of fleeing from Athens.

These introductory remarks are designed to show that there is a long tradition of recording and disseminating information at the Agora. At the present time, the question is how best to record the progress of the excavations of this great site, and how best to disseminate and share the results with the public at large.

For the first 90 years the answer was easy: we did it the way we always had. The records in the field were kept manually, in notebooks, supplemented by hand drawings and printed photographs. Inside the storage rooms and offices, the huge volume of material found was processed under the watchful eye of Lucy Talcott, an extraordinary woman who thought like a computer already in the 1930s. The records of the Agora Excavations are a marvel of referencing, cross-referencing, and retrieval of information. They also make it possible to recover the context of every object found, with objects recorded by elevation and within a one meter grid.

Using this system, dozens of scholars could write publications about different classes of antiquities, most of which became standard works in their respective fields. The full bibliography of Agora scholarship now runs to over 450 articles and 60 large volumes. All of which, today, will go comfortably on a small hard drive that will fit in your pocket.

In recent years, with the support of the Packard Humanities Institute and under the guidance of Bruce Hartzler, we have been changing how we record our excavations and considering new ways to share our results. The entire collection of objects is now catalogued in a database, integrated with field notes, photography, and conservation records. We have also been experimenting with applications of newer technology in the field, and now use total stations, laptops, digital cameras, and iPads to record the progress of excavation, to map the site, and to locate the position of finds.

We have not entirely abandoned the old system. Partially because the director remains somewhat old-fashioned in his views and limited in his abilities to apply the new technologies. But also for archival purposes. We know what a 90-year-old notebook looks like and we know that it can still be used. I doubt many can tell us where the developing technology can take us in 90 months, let alone years. So for the moment, parallel paper records are being maintained in the old manner, so we can afford to experiment, without losing the basic data.

For the greater public, our goal is to open the records as fully as practicable. For material that is unpublished, the intellectual property rights are reserved for the scholar who has been assigned the publication. Once presented, however, we see no reason why the material should not be available to anyone online. There can be little justification for the time, effort, and money that goes into excavation if the results are not made widely available.

For years, parallel to the scholarly tomes, picture books have been produced, written and extensively illustrated specifically for the layman and designed with the general public in mind. Twenty-seven have been published thus far, all presently available online. We continue to explore ways to have most of our findings available. Any attempts to stem the flow of information or try to benefit financially from it will surely prove to be counterproductive.

In short, both internally and externally, the Athenian Agora Excavations of the American School of Classical Studies in Greece are in a period of transition from old ways to new. We take comfort from the fact that throughout the centuries one of the prime purposes of an agora was the exchange and dissemination of information.

Privacy Policy

The Agora Notebooks app does not collect any personal information about you.

Acknowledgments

Created by Bruce Hartzler. Special thanks goes out to Georgios Verigakis. To the notebook annotation team: Anna Argyropoulos, James Artz, Panagiotis Athanasopoulos, Afroditi Chatzoglou, Leslie Feldballe, Tasos Frangou, Nadia Koutsina, Pia Kvarnstrom, Kris Lorenzo, Vassilis Tsiairis, Lucie Vidlickova. To the field supervisors, assistants, and diggers at the Athenian Agora Excavations who have provided valuable testing and feedback, especially Mike Laughy, Matt Baumann, Laura Gawlinski, Brian Martens, Nicholas Seetin, Marcie Handler, Daniele Pirisino, and Johanna Hobratschk. To the Agora staff members for their continuing support of the excavations: Craig Mauzy, Sylvie Dumont, Aspasia Efstathiou. To Anne Hooton for creating the application icon and color palettes. To Molly Richardson for her sublime editing skills. And to John Camp, the excavation director, for his constant and enthusiastic support of this project.